“Hostile to the past, inpatient of the present, and cheated of the future”: Albert Camus' The Plague and COVID-19

/Albert Camus’ The Plague was published over seventy years ago, but it has become very timely again. It deals with quarantine and isolation, faulty government response, how people interact with each other in times of crisis, and as the book’s title implies, illness and death.

As one commentator stated:

Whether or not you’ve read The Plague, the book demands reading, or rereading, at this tense national and international moment, as a new disease, COVID-19, caused by a novel form of coronavirus, sweeps the globe…. Workplaces, schools and colleges have closed or gone online; events have been canceled; and non-essential travel has been prohibited…. You may find yourself with more time to read than usual. Camus’s novel has fresh relevance and urgency—and lessons to give.

According to Morning Call, “Sales of The Plague have gone through the roof, and amazon.com reports that it is out of stock. Penguin Books is rushing more copies into print. In Italy, the hardest hit country in Europe by the coronavirus, The Plague has become a best seller. “

An article on NPR’s webpage states, “[In France,] you can’t pick up a newspaper without seeing a reference to the novel. People are saying in the French press, what do you absolutely need to read in this time? You need to read The Plague. ‘Almost as though this novel were a vaccine — not just a novel that can help us think about what we’re experiencing, but something that can help heal us.’”

The title of this post:

“Hostile to the past, inpatient of the present, and cheated of the future,”

is a quote from the book.

In this time when those coming of age will never have a prom or graduation, athletes are not allowed to compete, musicians are not allowed to perform, businesses can’t stay open or afford to keep on their employees, and everyone is isolated from friends and those they love, the quote seems particularly poignant.

We are standing in place when we want to be moving forward.

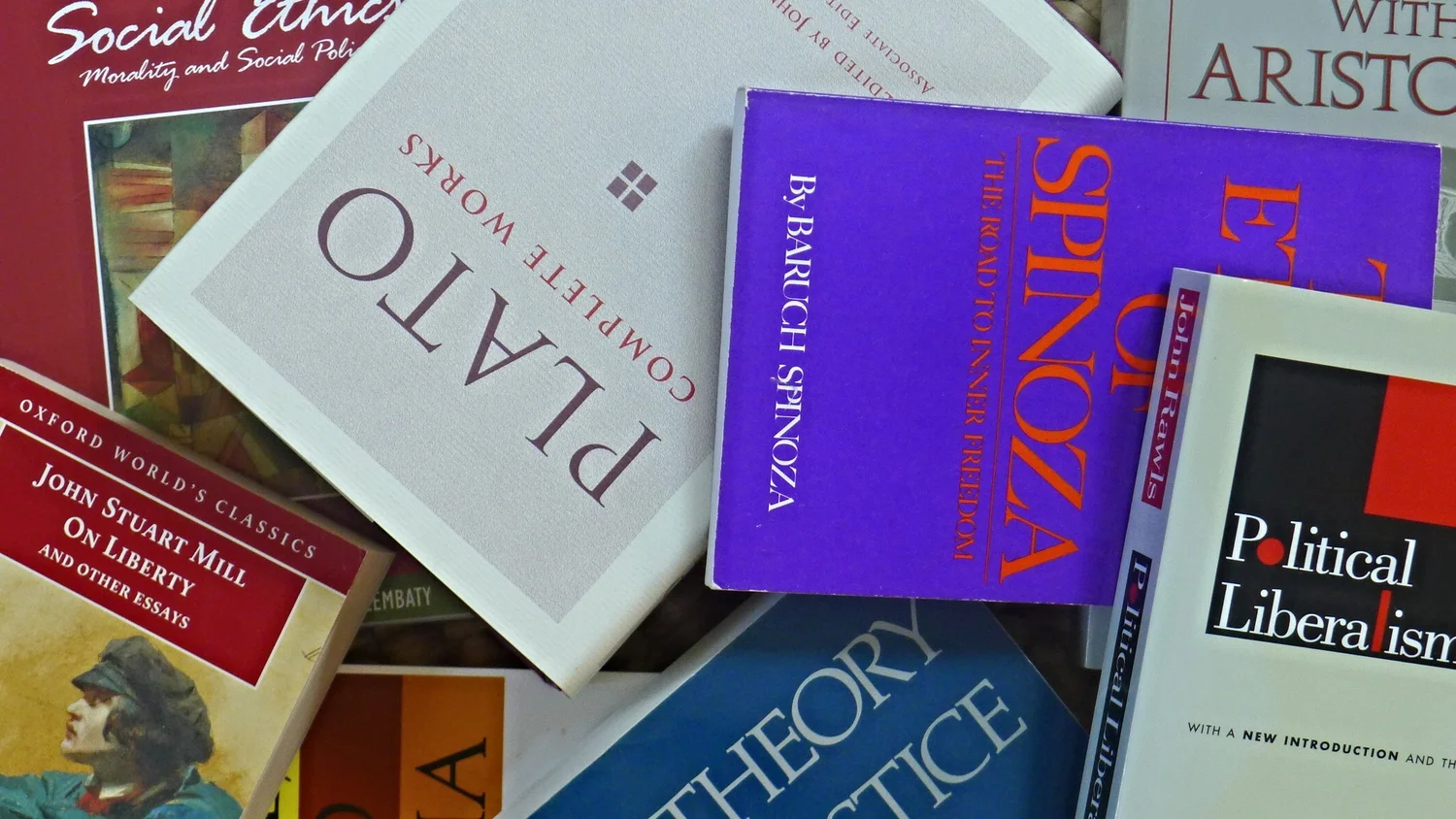

My copy of The Plague, which I found several decades ago, while a Freshman in college, in a box of books thrown away on the street in Philadelphia.

RELEVANCE AND METAPHORS

Perhaps the most succinct and poetic analysis comes from philosopher and noted essayist Alain de Botton, who writes in a March 22, 2020 New York Times article:

As the book opens, an air of eerie normality reigns. The town’s inhabitants lead busy money-centered and denatured lives. Then, with the pacing of a thriller, the horror begins. The narrator, Dr. Rieux, comes across a dead rat. Then another and another. Soon an epidemic seizes Oran, the disease transmitting itself from citizen to citizen, spreading panic in every street….

Camus was not writing about one plague in particular, nor was this narrowly, as has sometimes been suggested, a metaphoric tale about the Nazi occupation of France. He was drawn to his theme because he believed that the actual historical incidents we call plagues are merely concentrations of a universal precondition, dramatic instances of a perpetual rule: that all human beings are vulnerable to being randomly exterminated at any time, by a virus, an accident or the actions of our fellow man….

For Camus, when it comes to dying, there is no progress in history, there is no escape from our frailty. Being alive always was and will always remain an emergency; it is truly an inescapable “underlying condition.” Plague or no plague, there is always, as it were, the plague, if what we mean by that is a susceptibility to sudden death, an event that can render our lives instantaneously meaningless.

This is what Camus meant when he talked about the “absurdity” of life. Recognizing this absurdity should lead us not to despair but to a tragicomic redemption, a softening of the heart, a turning away from judgment and moralizing to joy and gratitude.

“The Plague” isn’t trying to panic us, because panic suggests a response to a dangerous but short-term condition from which we can eventually find safety. But there can never be safety – and that is why, for Camus, we need to love our fellow damned humans and work without hope or despair for the amelioration of suffering. Life is a hospice, never a hospital….

Camus speaks to us in our own times not because he was a magical seer who could intimate what the best epidemiologists could not, but because he correctly sized up human nature. He knew, as we do not, that “everyone has it inside himself, this plague, because no one in the world, no one, is immune.”

In an article on the Conversation web page, the unnamed author states:

Rereading The Plague over these past weeks has been an uncanny experience. Its fictive chronicle of the measures taken in the city of Oran against a death-dealing disease that strikes in 1940 sometimes seemed to blur into the government announcements reshaping our lives.

Oran is a city like anywhere else, Camus’ narrator tells us:

“Our citizens work hard, but solely with the object of getting rich. Their chief interest is in commerce, and their chief aim in life is, as they call it, ‘doing business.’”

Like people anywhere else, the Oranians are completely unprepared when rats begin emerging from the sewers to die in droves in streets and laneways. Then, men, women and children start to fall ill with high fever, difficulties breathing and fatal buboes.

The people of Oran initially “disbelieved in pestilences”, outside of the pages of history books. So, like many nations in 2020, they are slow to accept the enormity of what is occurring. As our narrator comments dryly: “In this respect they were wrong, and their views obviously called for revision.”

The numbers of afflicted rise. First slowly, then exponentially. By the time the plague-bearing spring gives way to a sweltering summer, over 100 deaths daily is the new normal.

Emergency measures are rushed in. The city gates are shut, and martial law declared. Oran’s commercial harbor is closed to sea traffic. Sporting competitions cease. Beach bathing is prohibited.

Soon, food shortages emerge (toilet paper, thankfully, is not mentioned). Some Oranians turn plague-profiteers, preying on the desperation of their fellows. Rationing is brought in for basic necessities, including petrol.

Meanwhile, anyone showing symptoms of the disease is isolated. Houses, then entire suburbs, are locked down. The hospitals become overwhelmed. Schools and public buildings are converted into makeshift plague hospitals….

In these circumstances, fear and suspicion descend “dewlike, from the greyly shining sky” on the population. Everyone realizes that anyone – even those they love – could be a carrier.

Come to think of it, so could each person themselves….

Separation, isolation, loneliness, boredom and repetition become the shared fate of all.

In Oran, places of worship go empty. Funerals are banned for fear of contagion. The living can no longer even say farewell to their many dead.

This article also describes multiple levels of allegory in the novel. The first level is plague as metaphor for the Nazi occupation of France:

The sanitary teams reflect Camus’ experiences in, and admiration for, the resistance against the “brown plague” of fascism.

Camus’ title also evokes the ways the Nazis characterized those they targeted for extermination as a pestilence. The shadow of the then-still-recent Holocaust darkens The Plague’s pages.

When death rates become so great that individual burials are no longer possible – as in scenes we are already seeing – the Oranaise dig collective graves into which:

“the naked, somewhat contorted bodies were slid into a pit almost side by side, then covered with a layer of quicklime and another of earth […] so as to leave space for subsequent consignments.”

When this measure fails to keep up with the weight of these “consignments”, as with the genocidal actions of the Einzatsgruppen, “the old crematorium east of the town” is re-purposed. Closed streetcars filled with the dead are soon rattling along the old coastal tramline:

“Thereafter, […] when a strong wind was blowing […] a faint, sickly odor coming from the east remind[ed] them that they were living under a new order and that the plague fires were taking their nightly toll.”

The next level of metaphor deals with:

[T]he force of what Dr Rieux calls “abstraction” in our lives: all those impersonal rules and processes which can make human beings statistics to be treated by governments with all the inhumanity characterizing epidemics.

For this reason, the enigmatic character Tarrou identifies the plague with people’s propensity to rationalize killing others for philosophical, religious or ideological causes. It is with this sense of plague in mind that the final words of the novel warn:

“that the plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good; that it can lie dormant for years and years in furniture and linen-chests; that it bides its time in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, and bookshelves; and that perhaps the day would come when, for the bane and the enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city.”

Finally, the novel can be viewed as a “sermon of hope” (as it was described by Irish author Conor Cruise O’Brien) as well as a call for what the article’s author terms “unheroic heroics.”

In the end, the plague dissipates as unaccountably as it had begun. Quarantine is lifted. Oran’s gates are reopened. Families and lovers reunite. The chronicle closes amid scenes of festival and jubilation.

Camus’ narrator concludes that confronting the plague has taught him that, for all of the horrors he has witnessed, “there are more things to admire in men than to despise”.

Unlike some philosophers, Camus became increasingly skeptical about glorious ideals of superhumanity, heroism or sainthood. It is the capacity of ordinary people to do extraordinary things that The Plague lauds. “There’s one thing I must tell you,” Dr. Rieux at one point specifies:

“there’s no question of heroism in all this. It’s a matter of common decency. That’s an idea which may make some people smile, but the only means of fighting a plague is common decency.”

It is such ordinary virtue, people each doing what they can to serve and look after each other, that Camus’ novel suggests alone preserves peoples from the worst ravages of epidemics, whether visited upon them by natural causes or tyrannical governments.

It is therefore worth underlining that the unheroic heroes of Camus’ novel are people we call healthcare workers. Men and women, in many cases volunteers, who despite great risks step up, simply because “plague is here and we’ve got to make a stand”.

It is also to these people’s examples, The Plague suggests, that we should look when we consider what kind of world we want to rebuild after the gates of our cities are again thrown open and COVID-19 has become a troubled memory.

IS CAMUS SUSPICIOUS OR TRUSTING? IS HE A PESSIMIST OR OPTIMIST?

A novel about a plague may seem like a depressing undertaking, and it is, for the most part.

David A. Schultz, for Counterpunch, describes the milieu out of which the novel grew, which partially explains the feeling of paranoia throughout the novel:

[Camus, while] born in Algeria, was in Paris when the Nazis invaded, fleeing the city and becoming a member of the resistance and underground….

As part of the French Underground [he] had to constantly fear others. Who were your friends or enemies? Could someone you thought be loyal really be a spy or simply turn on you for no apparent reason. Instead of finding comfort in others the French Resistance instilled a sense of paranoia and fear of others. The look of others, their close contact, or trusting them too much could result in a betrayal.

Fear of the other is central [to] The Plague. Here, a fictionalized account of a plague spread by rats running rampant through a community spews fear of one another as they are seen as a source of disease.

He has an insight into the anomalies in the lives of the people here who, though they have an instinctive craving for human contacts, can’t bring themselves to yield to it, because of the mistrust that keeps them apart. For its common knowledge that you can’t trust your neighbor; he may pass the disease to you without your knowing it, and take advantage of a moment of inadvertence on your part to infect you.

This distrust of others can lead to xenophobia, as noted by Liat Collins:

Throughout the West, [because the virus initially broke out in Wuhan, China,] anybody with Asian features immediately became suspect. Native Parisians of Asian ethnicity told how their French compatriots avoided sitting next to them on buses and on the Metro. The same story in London, Berlin and Barcelona. Had the disease started in the US or some other Western country, would train passengers have ignored seats next to all English-speakers?

Although the novel portrays fear of the other, it also shows the sense of community that can arise out of shared sacrifice. Sean Illing deals with this perceptively in his article, “What Albert Camus’s “The Plague” can teach us about life in a pandemic.” According to Illing:

The main thing about a pandemic like the novel coronavirus is that it doesn’t discriminate.

Whoever you are, wherever you live, you’re vulnerable, at least in principle. While some of us may fare better because of our age or health, the microbes themselves are impartial.

It’s worth pausing to reflect on the implications of that fact. Among other things, it means we’re all in the same boat, for better or worse. But accepting this — really accepting this — seems uniquely difficult in America.

This country is built on a cult of individualism. It’s a myth so deeply ingrained that it’s politically toxic to even question it, as President Barack Obama learned back in 2012 when he committed the crime of stating the obvious:

“If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a business, you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen.”

Obama’s remarks became “A Thing” in conservative media and “You didn’t build that” was a popular refrain at the Republican National Convention that year. Obama wasn’t denying that individual effort and talent matter. His point was that we’re all embedded in a broader social system, and our lives are contingent, one way or another, on the work of other people. That an observation so banal could generate so much controversy speaks to how deep the individualist ethos goes.

But the crisis we’re facing now, a rapidly spreading pandemic, explodes this ethos. No one can deal with this threat in a vacuum. Sure, there are steps you can take to protect yourself and your family, but your best efforts are less likely to matter if your neighbors, your community, your government, don’t do their part.

Even if you’re young and healthy, you’ll become a vector for spreading the disease to others if you’re not mindful about what you do or where you go. And if you don’t modify your behaviors and needlessly get sick, you’ll increase the pressure on an already overtaxed health care system and jeopardize the care of someone else who might need it more than you.

Illing goes on (as promised in the title of his article) to explain what The Plague can teach us in this time of crisis:

A plague is an extraordinary event, and the horror it unleashes is extraordinary, too. But suffering is anything but extraordinary. Every single day you leave the house, something terrible could happen. At any moment, you could get mortally sick. The same is true for everyone you know. All of us are hostages to forces over which we have no control.

A pandemic simply foregrounds what’s already true of our condition. And it forces us to think about our responsibilities to the people around us. One of the reasons I love The Plague is that it draws out the conflict between individual happiness and moral obligation in such vivid fashion. The hero of The Plague is a committed doctor named Rieux. From the very beginning, Rieux devotes himself to resisting the plague and achieving solidarity with its victims. His sense of purpose is wrapped up in struggle and sacrifice demanded by the sickness.

Each character in the story is defined by what they do when the scourge comes. No one escapes it, but those who revolt against it, who reduce the suffering of others, are the most fulfilled. The only villains in The Plague are those who cannot see beyond themselves. The plague, for these people, is either an excuse to flee or an opportunity to exploit. What makes them so awful isn’t their self-interest; it’s what their self-interest undermines. Because they can’t see that their condition is shared, an ethos of solidarity is completely foreign to them. And that blindness makes community — real community — impossible.

A recurring theme of The Plague is that crises have a way of upending the social order. It throws almost everything we take for granted into chaos. And it forces us to attend to the present moment. Nothing else really matters when your day-to-day survival is at stake. There’s just here and now and, as Rieux says, “We’re all involved in it.”

The coronavirus isn’t “The Big One.” It won’t be the end of us. But it will demand the kind of solidarity our individualist ethos denies….

The lesson of The Plague is that we should see ourselves as members of a community, not as atomized actors. And that means when we think of “preparedness,” we’re thinking not just of ourselves but of how our actions will affect other people. It means thinking of risk as more than an individual calculation.

A pandemic, terrible though it is, highlights our mutual interdependence in a way that only tragedy can. The beauty of The Plague is that it asks the reader to map the lessons of the pandemic onto everyday life. The principles that drive the hero, Rieux, are the same principles that make every society worthwhile — empathy, love, and solidarity.

If we learn these lessons now, in a moment of crisis, we’ll all be better off on the other side of it.

Liesl Schillinger has also commented on the sense of community that shared tragedies evoke:

[The plague’s] catastrophe is collective: “a feeling normally as individual as the ache of separation from those one loves suddenly became a feeling in which all shared alike,” Camus writes. This ache, along with fear, becomes “the greatest affliction of the long period of exile that lay ahead.” Anyone who lately has had to cancel a business trip, a class, a party, a dinner, a vacation, or a reunion with a loved one, can feel the justice of Camus’s emphasis on the emotional fallout of a time of plague: feelings of isolation, fear, and loss of agency. It is this, “the history of what the normal historian passes over,” that his novel records, and which the novel coronavirus is now inscribing on current civic life.

“A feeling normally as individual as the ache of separation from those one loves suddenly became a feeling in which all shared alike,” Camus writes.

If you read The Plague long ago, perhaps for a college class, you likely were struck most by the physical torments that Camus’s narrator dispassionately but viscerally describes. Perhaps you paid more attention to the buboes and the lime pits than to the narrator’s depiction of the “hectic exaltation” of the ordinary people trapped in the epidemic’s bubble, who fought their sense of isolation by dressing up, strolling aimlessly along Oran’s boulevards; and splashing out at restaurants, poised to flee should a fellow diner fall ill, caught up in “the frantic desire for life that thrives in the heart of every great calamity”: the comfort of community. The townspeople of Oran did not have the recourse that today’s global citizens have, in whatever town: to seek community in virtual reality. As the present pandemic settles in and lingers in this digital age, it applies a vivid new filter to Camus’s acute vision of the emotional backdrop of contagion.

Today, the exile and isolation of Plague 2.0 are acquiring their own shadings, their own characteristics, recoloring Camus’s portrait. As we walk along our streets, go to the grocery, we reflexively adopt the precautionary habits social media recommends: washing our hands; substituting rueful, grinning shrugs for handshakes; and practicing “social distancing.” We can do our work remotely to avoid infecting others or being infected; we can shun parties, concerts and restaurants, and order in from Seamless. But for how long? Camus knew the answer: we can’t know.

Like the men and women who lived in a time of disruption almost a century ago, whom Camus re-imagined to illustrate his ineradicable theme, all we can know is that this disruption will not last forever. It will go, “unaccountably,” when it pleases. And one day, others will emerge. When they do, his novel warned long ago, and shows us even more clearly now, we must take care to read the “bewildering portents” correctly. “There have been as many plagues as wars in history,” Camus writes. “Yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise.”

Matt Winisett, writing for the National Review, finds as did the above authors The Plague “edifying reading in this time of quarantine”:

Not simply because its plague eventually subsides — all plagues eventually do — but because Camus’s novel provides a guide for living amid such upheaval. Its advice can be quite practical: “Each of us has the plague within him,” Tarrou says, so “we must keep endless watch on ourselves lest in a careless moment we breathe in somebody’s face and fasten the infection on him.” These instructions are much more vivid than our ubiquitous directives to “practice social distancing.”

It’s the underlying message, however, that makes The Plague a classic. The illness is the main antagonist, but also an afterthought, a plot device to torment Oran’s residents and reveal life’s fundamentally absurd nature: We can all be struck down on a whim without warning, and through our own careless actions we can strike down others without cause or even intent. We all carry the plague, this capacity for evil and destruction, within us. (As Christians would say, we are all fallen creatures.) Given that, the relevant question becomes not how to eradicate it — we can’t — but how to live with our knowledge of it.

“There’s no question of heroism in all this,” Rieux says. Living a worthy life does not require too much. “The only means of fighting a plague,” he says, “is common decency.” For Rieux, that means simply doing his job and continuing to treat patients. For others, the responsibility seems even less burdensome. “All I maintain,” Tarrou says, in perhaps the novel’s most famous passage, “is that on this earth there are pestilences and there are victims, and it’s up to us, so far as possible, not to join forces with the pestilences.” But the simplicity of this moral belies its challenge. Siding with the victims and fighting for the innocent does not come naturally to us; the truth is closer to the opposite. “What’s natural is the microbe,” Tarrou continues. “All the rest — health, integrity, purity (if you like) — is a product of the human will, of a vigilance that must never falter.”

Intentionally or not, Camus’s ostensibly agnostic philosophy evokes G. K. Chesterton’s Christianity. “It is always simple to fall,” Chesterton wrote in Orthodoxy. “There are an infinity of angles at which one falls, only one at which one stands.” In either worldview, existentialist or Christian, the instructions are the same. Living well, like living hygienically, doesn’t require checking the boxes off a list of unattainable virtues — just ceaseless, vigilant attention to deceptively challenging commandments. Wash your hands. Avoid touching your face. Love thy neighbor. Don’t join with the pestilences. Ultimately, Camus writes, “The good man, the man who infects hardly anyone, is the man who has the fewest lapses in attention.”

Roger Lowenstein, for the Washington Post, writes:

[T]he satisfying surprise for me, rereading “The Plague” a half-century after my first encounter with it, is that Camus… fashioned from this morbid allegory a theme of human goodness. It is a redemptive book, one that wills the reader to believe, even in a time of despair. Rieux and the priest cannot resolve the eternal question of whether a God could allow such a blight, but to Rieux, the answer is simple: In the absence of an all-responsive deity, he must make his rounds, cure whom he might. As with all evils, he says, “It helps men to rise above themselves.”

This is true for Rieux, and for some of the lesser townsfolk, who overcome their selfish desires and lend a hand, only to discover that if happiness is shameful by oneself, fear is more bearable when it is shared. To this, the veiled narrator has chosen to bear witness. His mission, he ultimately declares, is to state what we learn in a time of pestilence: “There are more things to admire in men than to despise.”

HOW SERIOUS IS THE DANGER OF COVID-19, REALLY?

In February 2020, before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, it was common to hear people denigrate the seriousness of the danger. For example, one commentator begins his article with a touch of good natured humor, but ends by saying that the “world has gone overboard”:

Current events made me dust off my collection of Albert Camus books. The compendium has been sitting on my shelf for a while. The dust made me sneeze and I instantly reflected that it was lucky I was still in the comfort of my living room. If you sneeze while reading on a bus – or in any public place – you get dirty looks. Such looks don’t kill, but those who give them are acting out of deadly fear. Coronavirus, Covid-19, or whatever it is being called now, has spread panic around the global village. I’m not immune to fear – nor presumably to the disease – but I think the world has gone overboard.

He goes on to say:

The virus has brought out the best and worst in people. We’ve all been exposed to the hysteria, if not the disease itself. When China sneezes, the whole world goes cold with fear. This might be one of the biggest collective panic attacks we’ve ever known. The disease should go down in history for that alone.

In an article in The Atlantic, the author makes interesting points relating to the different “logics” of science and art, but also suggests that perhaps the danger with COVID-19 is not as serious as it is made out to be:

Anyone in a position of authority—running a school, a business, or an organization—turns to experts at moments like this….

Their cool balance, which must inform any decision making, rests on a logic of rationality and science. And one must heed it. Yet one must also heed a very different logic, the one captured by artists, poets, and storytellers….

The coronavirus will not be as bad as [the plague described in Edgar Allan Poe’s Masque of the Red Death], we can be quite sure, but what Poe—and, in a different way, Camus and many others—captured is the logic of fear and dread that is also part of an epidemic. And that logic is ignored at our peril too. Walk through crowded airports, and you will see useless masks adorning the faces of people who are undoubtedly quite well. Talk to chief executives, and they will tell you of stockpiling vitamin C and canceling all foreign travel. Meet a cosmopolitan friend, and he will embarrassedly refuse to shake hands, preferring to wai, Thai style (a palm-to-palm salute), or put his right hand to his heart (Arabic style), or simply bump elbows (an American innovation).

The statistics about the relatively low mortality rates of the coronavirus, the more ominous term that normal people use, and the unquestionably more deadly toll to date of the common flu are undoubtedly true, and in some measure beside the point. The technocratic impulse is to damp down unreasoning fear with an antiseptic spray of statistics, or if that fails, simply to shrug one’s shoulders and dismiss the foolish anxieties of ignorant people. Neither will quite do the job.

Why do we fear the coronavirus more than the common flu? Perhaps because even if we fail to get our annual flu shot, we know that such a thing exists. And even if one side of our brain knows that the cocktail that goes into this year’s vaccine is a gamble on the part of the pharmaceutical companies, which may be more or less effective, the other side is saying: The threat is, if not under control, controllable. The coronavirus, like the plague of old, does not feel that way. It does not feel controllable, because it is not. Indeed, the main resort seems to be a centuries-, perhaps millennia-old response: quarantine. And even that proves leaky in an age of ever-expanding travel and human contact.

We live in an era when the masters of Big Data, be they in corporations or political campaigns, know an appallingly large amount about each and every one of us: our tastes, our prejudices, our aversions, our vulnerable points. They spend a great deal of effort on manipulating us, apparently with success. There are social scientists who believe that this data can and indeed should be used to nudge us into healthy or commendable forms of behavior. And in an era of ubiquitous facial-recognition software, we are all, in some measure, perpetually under surveillance.

But somehow, the plague creeps in behind the precisely targeted Facebook ads, and human beings must confront the limits of their ability to control events, and the primordial fear that a friend — or worse, a loved one — could, in an invisible and wholly unintended way, cause our deaths. Governments and businesses that pride themselves on their ability to exert control are at the mercy of individuals who have incentives to misrepresent the truth or temporarily suppress it. Face a population fearful of epidemic, and you face, potentially, an angry and uncontrollable mob.

The coronavirus can bring ugly deaths, and has done so to some of the doctors and nurses attempting to contain it. It is nothing like the real plague, with blackened buboes and excruciating death agonies. But it is scary enough, and if it’s true that the mortality rate is 2 percent, or even half that, and if the hasty quarantines being thrown up everywhere fail to work, the chances are that many of us will know someone who dies from it.

In our rational, technocratic way, we will of course find countermeasures and even celebrate them as accelerators of progress. Schools and businesses are learning how to exploit teleconferencing in ways that will improve our ability to teach and work together in cyberspace, which is a good thing. We are all learning (the hard way, admittedly) about the vulnerability of global supply chains, and will make them more resilient in the coming months and years. And there is nothing like a good scare to improve one’s institutional contingency planning for the next time, as the British government discovered after the Munich crisis of 1938.

All true, and all necessary. But as we react to this problem with the tools of medical science and dispassionate thought, we should periodically check ourselves — not so much for fever, but for the arrogance of Prince Prospero, and for the illusion of control that set him and his guests up for a ghastly end. The truth is, we live in the midst of multiple plagues — after all, it is considered a good thing when your tweet “goes viral.” We would be wisest if we could react to all those plagues with the unillusioned heroic calm of Camus’ hero Dr. Rieux, who has “no idea what’s awaiting me, or what will happen when all this ends,” and who will simply go about his business of curing those he can, and comforting those he cannot.

Another commentator writes:

Be assured, before you take up this book, that however fearful COVID-19 may be, it is nowhere near as destructive as Camus’s plague…. Even when treated with antibiotics it has a death rate of 10 percent; and if untreated, up to 90 percent. Coronavirus is not remotely like that.

COVID-19 is doubtless less lethal than the bubonic plague, but at this point in time, it is certainly lethal enough to take seriously, without any hint to justify those who may question its seriousness.

The World Economic Forum sponsored a study that investigated the economic impacts of the Spanish Flu. This study yielded two main insights. First, areas that were more severely affected by the 1918 Flu saw a sharp and persistent decline in real economic activity. Second, cities that implemented early and extensive non-pharmaceutical interventions (such as social distancing) suffered no adverse economic effects over the medium and long terms.

Also, although COVID-19 may not be as lethal as the Spanish Flu, its financial damage may end up being far worse. According to the Wall Street Journal:

The coronavirus has unleashed a massive economic shock on the U.S. and the world. It began with disruptions to supply chains and restrictions on travel and is now rapidly expanding via spontaneous and government-imposed “social distancing” measures such as closing schools and confining regional populations to their homes. Entire industries are shutting down….

There is no clear historical precedent for the scale and nature of this shock. Some economists see U.S. output falling by more in the coming quarter than in the worst quarter of the 2008-09 recession. Nonetheless, previous episodes of pandemics, disasters and crises offer clues about what to expect, how policy makers make matters better or worse and the likely long-term consequences.

A few lessons stand out. First, governments and the public always face a trade-off between economic stability and public health and safety. The more they prioritize health and safety, the bigger the near-term cost to the economy, and vice versa.

Second, at the outset of the disaster, policy makers are coping with enormous uncertainty. Early responses are often timid or off-target and more sweeping action is delayed by political disagreement.

“We learned that we need to prioritize speed, think in tranches, be visible and worry about how to pay for it later,” said Tim Adams who served in the Treasury Department during 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina and is now president of the Institute of International Finance. “If you wait to craft the perfect response, you’ll lose valuable time and you’ll miss something no matter what.”

Third, disasters often create permanent changes to habits, and the most affected industries and regions can take years to recover. New Orleans’ population has steadily regained ground since falling by half after Hurricane Katrina but isn’t yet back to its pre-storm level. But for society as a whole, the scars heal remarkably quickly. Humans are immensely adaptable.

While the coronavirus isn’t a flu virus, the pandemic resembles the influenza pandemics of the 20th century, in that it is highly infectious and relatively lethal. The deadliest was the Spanish flu in 1918, which infected at least 500 million people world-wide (more than a quarter of the Earth’s population) and killed 50 million or more, including 675,000 in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Yet the economic impact was surprisingly mild. The National Bureau of Economic Research says a recession began in August 1918 and ran through the next March. The flu probably wasn’t the cause. In a 2006 paper for Canada’s Department of Finance, Steven James and Tim Sargent found little trace of the pandemic in international trade, retail sales, railroad passenger traffic and stock prices. They saw some effect on industrial production, which fell sharply in October and November but that was in part due to falling defense production as World War I drew to a close. They put the pandemic’s effect at a 0.5% decline in annual output.

There are likely several reasons. Far fewer people worked in jobs that required close social contact. Farming, fishing and forestry accounted for 16% of American occupations in 1910 compared with 0.3% in 2004, according to Messrs. James and Sargent. Few workers had sick leave, and unemployment insurance didn’t exist. Thus, workers who were sick or at risk could seldom afford to stay home.

The second is that governments, many preoccupied with war, didn’t put the same weight on stopping the epidemic as they do now. The federal government had little formal role fighting infectious disease. President Woodrow Wilson never publicly mentioned the epidemic, John Barry writes in “The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History.” Chicago’s public health commissioner flatly rejected closing businesses, Mr. Barry wrote, quoting him as saying: “It is our duty to keep the people from fear. Worry kills more people than the epidemic.”

Cities that took that attitude saw higher death tolls, according to a 2007 study by Richard J. Hatchett, Carter E. Mecher, and Marc Lipsitch. Philadelphia waited 16 days before restricting social gatherings, even allowing a parade to go ahead. St. Louis took just two days. The daily death rate from the epidemic peaked at a level five or more times higher in Philadelphia than in St. Louis.

The lesson: The more short-term economic pain Americans are willing to endure, the more lives they will save.

The article also looks at the Asian Flu of 1957, the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, and the Japanese earthquake and nuclear meltdown of 2011, and concludes:

The [above] disasters illustrate the tensions between balancing the public’s legitimate aversion to harm against the known consequences and likely economic costs. Until recently, the coronavirus seemed to present the opposite risk: The public wasn’t taking the threat seriously enough, forcing the government to take more disruptive steps, to limit human interaction, while seeking to offset the resulting economic cost through fiscal and monetary policy.

As in all these past disasters, the coronavirus pandemic confronts governments, business and the public with crippling uncertainty and painful trade-offs. The main difference is that this is on a scale and breadth never seen in living memory.

HISTORY OF “PESTILENCE FICTION”

The Plague, given all the interest it has received lately, has been described as leading a ““surge in pestilence fiction.”

Jill Lepore, in an article in the New Yorker, “What Our Contagion Fables Are Really About,” provides a mini-history of “pestilence fiction.”

She begins with Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year, which was written in 1722.

As she says:

Reading is an infection, a burrowing into the brain: books contaminate, metaphorically, and even microbiologically. In the eighteenth century, ships’ captains arriving at port pledged that they had disinfected their ships by swearing on Bibles that had been dipped in seawater. During tuberculosis scares, public libraries fumigated books by sealing them in steel vats filled with formaldehyde gas….

But, of course, books are also a salve and a consolation. In the long centuries during which the plague ravaged Europe, the quarantined, if they were lucky enough to have books, read them. If not, and if they were well enough, they told stories. In Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, from the fourteenth century, seven women and three men take turns telling stories for ten days while hiding from the Black Death.

According to Lepore:

Stories about plagues run the gamut from “Oedipus Rex” to “Angels in America.” “You are the plague,” a blind man tells Oedipus. “It’s 1986 and there’s a plague, friends younger than me are dead, and I’m only thirty,” a Tony Kushner character says. There are plagues here and plagues there, from Thebes to New York, horrible and ghastly, but never one plague everywhere, until Mary Shelley decided to write a follow-up to “Frankenstein.”

“The Last Man,” which is set in the twenty-first century, is the first major novel to imagine the extinction of the human race by way of a global pandemic. Shelley published it at the age of twenty-nine, after nearly everyone she loved had died, leaving her, as she put it, “the last relic of a beloved race, my companions, extinct before me.” ….

[I]n the year 2092, the plague arrives, ravaging first Constantinople. Year after year, the pestilence dies away every winter (“a general and never-failing physician”), and returns every spring, more virulent, more widespread. It reaches across mountains, it spreads over oceans…. Inevitably, the plague comes, at last, to England, but by then the healthy have nowhere left to go, because, in the final terror of pandemic, there is “no refuge on earth”: “All the world has the plague!” ….

The great dream of the Enlightenment was progress; the great dread of epidemic is regress. But in American literature such destruction often comes with a democratic twist: contagion is the last leveler. Edgar Allan Poe’s 1842 tale “The Masque of the Red Death” is set in a medieval world plagued by a contagious disease that kills nearly instantly….

Poe’s red death becomes a pandemic in Jack London’s novel “The Scarlet Plague,” serialized in 1912…. The plague had come in the year 2013, and wiped out nearly everyone, the high and the low, the powerful nations and the powerless, in all corners of the globe, and left the survivors equal in their wretchedness, and statelessness. One of the handful of survivors had been a scholar at the University of California, Berkeley, a professor of English literature. When the disease hit, he hid out in the chemistry building, and turned out to be immune to the virulence…. When the novel opens, in the year 2073, the professor is a very old man, a shepherd, dressed in animal hide… and living like an animal. He tells the story of the scarlet plague to his grandsons, boys who “spoke in monosyllables and short jerky sentences”….

The structure of the modern plague novel, all the way to Stephen King’s “The Stand” and beyond, is a series of variations on “A Journal of the Plague Year” (a story set within the walls of a quarantine) and “The Last Man” (a story set among a ragged band of survivors). Within those two structures, though, the scope for storytelling is vast, and so is the scope for moralism, historical argument, and philosophical reflection. Every plague novel is a parable.

Albert Camus once defined the novel as the place where the human being is abandoned to other human beings. The plague novel is the place where all human beings abandon all other human beings. Unlike other species of apocalyptic fiction, where the enemy can be chemicals or volcanoes or earthquakes or alien invaders, the enemy here is other humans: the touch of other humans, the breath of other humans, and, very often—in the competition for diminishing resources—the mere existence of other humans.

[Lepore then discusses The Plague.]

Camus’s observation about “the utter incapacity of every man truly to share in suffering that he cannot see” is the subject of José Saramago’s brilliant and devastating reimagining of the plague tale, “Blindness,” from 1995, in which the Defoe-like doctor is an ophthalmologist and the disease that reduces humans to animals is the inability to see. As historical parable, “Blindness” indicts the twentieth-century authoritarian state: the institutionalization of the vulnerable, the ruthlessness of military rulers. When the disease strikes, the government rounds up all the blind and locks them up in a mental asylum, where, blindly, they go to war with one another. They steal, they rape. “The blind are always at war, always have been at war,” Saramago writes, in the novel’s darkest observation.

For Saramago, blindness isn’t a disease; blindness is the human condition. There is, in the novel, only one person left with sight. She reads to the blind, which, for them, is both a paradise and an exasperation: “This is all we are good for, listening to someone reading us the story of a human mankind that existed before us.” And that, in the modern plague novel, is the final terror of every world-ending plague, the loss of knowledge, for which reading itself is the only cure…. Puzzled by a patient who has come to his office after being stricken suddenly and inexplicably blind — he sees not black but only a milky whiteness — the eye doctor goes home and, after dinner, consults the books in his library. “Late that night, he laid aside the books he had been studying, rubbed his weary eyes and leaned back in his chair,” Saramago writes. He decides to go, at last, to bed. “It happened a minute later as he was gathering up the books to return them to the bookshelf. First he perceived that he could no longer see his hands, then he knew he was blind.”

Everything went white. As white as a blank page.

Although not included in Lepore’s history, other notable works of fiction dealing with “pestilence” are:

Sinclair Lewis’ Dodsworth, which deals with malaria,

Henrik Ibsen’s play An Enemy of the People, dealing with contaminated water at a public bath,

Katherine Ann Porter’s Pale Horse, Pale Rider, which deals with the Spanish Flu;

Michael Chricton’s Andromeda Strain, which is a science fiction novel dealing with a deadly extraterrestrial microorganism, and

although mentioned in Lepore’s article, they weren’t discussed in any detail:

Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, which deals with AIDS; and

Stephen King’s The Stand, which deals with a pandemic of a weaponized strain of influenza.

MISCELLANEOUS COMMENTS

Oliver Gloag writes:

Paradoxically, in these times of self-imposed exiles, school closings and quarantines, the coronavirus tells us about a different kind of globalization. We have now learned that China manufactures most of our medications and medical supplies – not only our consumer goods – and suddenly emerges in our mind the figure of a Chinese worker making our antibiotics and the like: this leads to the stark realization that our survival depends on hers; it is a collective enterprise. We are in it together. This could be the best thing that comes out of the current pandemic.

Liat Collins points out:

In its dystopian way, the novel also records the “fake news” produced by those in power and by the press….

Coronavirus broke out, as we all now know, in the commerce-focused Wuhan, China. The authorities at first denied its presence – “The usual taboo, of course; the public mustn’t be alarmed, that wouldn’t do at all,” as Camus puts it. In the real-life, modern version, the doctor who first discovered the contagion and dared to publish it was vilified, and punished. Although his good name was later restored, Dr. Li Wenliang, 34, died from the very virus he had warned of.

More than 45 million ordinary Chinese, in Wuhan and other cities in Hubei province, were put in an unprecedented isolation, just as the Chinese New Year of the Rat commenced. Many have noted that such a massive quarantine – some 11 million in a tight lockdown in Wuhan alone – could only happen in a dictatorship.

Others making the “fake news” parallel are: Bruce Frassinelli and Oliver Gloag.

Roger Lowenstein writes of “exile”:

Camus likened [living through the plague] to a state of “exile,” a familiar theme to the writer, for whom metropolitan France, where he spent his adult life, was never more than an adoptive home. In “The Plague,” exile is partly geographic, describing the painful isolation from those outside the city gates — but it refers, more powerfully, to exile in time.

The plague separates people from their former lives. Despite their fervent longings to go back, the past is suddenly alien — a detached memory. As the cranes on the wharves go silent and the death toll mounts, seemingly in time with the oppressive heat, people become fixed on “the ground at their feet.” The narrator — whose identify is long kept secret — stoically observes, “Each of us had to be content to live only for the day.”

Camus was preoccupied with the absurd — with Sisyphus condemned, like mankind, to pushing a stone up a hillside. In “The Plague” he found a lens for projecting life at once suspended and more vivid. Though Oran had become but a vast “railway waiting-room,” with all the boredom and indifference the metaphor implies, people were, at least, living in the present. The urgency of volunteering in sanitary squads replaces the yearning for a vaccine or the outside world. The present replaces the future. A mysterious observer trapped in Oran, to whose diary the narrator gains access, posits that only this — being “fully aware” of time — guarantees that it won’t be wasted.

Dr. Howard Markel, who teaches a class on literature and medicine at the University of Michigan, writes:

I was introduced to the novel while still in graduate school after reading an essay entitled “What Is an Epidemic?” by the eminent historian Charles Rosenberg. An intrepid scholar of the devastating cholera pandemics of 1833, 1849 and 1866, Rosenberg used Camus’ novel to characterize the unfolding of an epidemic as a dramatic set of events, usually in four acts, with a distinct but somewhat predictable narrative plot line.

And since I can no longer teach my students in person, I thought a cleaned up version of my tattered lecture notes — on Camus and Rosenberg — might be useful in recommending a good novel while we all shelter in place.

Here’s how it goes:

The first act is one of eye-opening shocks or events….

The second act of an epidemic centers on how society responds to a seemingly random, “out of the blue” event like an epidemic, and attempts to understand it….

Once an epidemic is recognized, the third act begins, and we watch the public demanding that some type of action of some kind be taken….

Life begins to return to its normal patterns, and healthy people begin to place the epidemic in the past.

The final act is perhaps the most vexing phase of an epidemic, especially for those involved in public health management and epidemic-preparedness planning. Epidemics often end as ambiguously as they appear. Specifically, once an epidemic peters out and susceptible individuals die, recuperate or escape, life begins to return to its normal patterns, and healthy people begin to place the epidemic in the past. Camus perfectly recorded this sense of “global amnesia” — a mind-set that threatens the world for pandemics to come:

… as he listened to the cries of joy rising from the town, Rieux remembered that such joy is always imperiled. He knew what these jubilant crowds did not know but could have learned from books: that the plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good; that it can lie dormant for years in furniture and linen-chests; that it bides its time in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, and bookshelves; and that perhaps the day would come when, for the bane and the enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city.

Epidemics and pandemics are living, social laboratories.

They provide windows on the resilience and efficiency of a particular society’s governmental structures, its social strengths and shortcomings, and its engagement with rumor, suspicion, or outright bad behavior. After all, epidemics are hardly quiet occasions; they are experienced and responded to in real time by the affected community and then later re-discovered, heralded, and explained by historians like me — as well as novelists.

As we reflect on how drastically COVID-19 has changed all of our lives, the final few sentences of Camus’ “The Plague” may well represent the saddest, and most eloquent, endings in modern literature.

David A. Schultz in “Camus and Kübler-Ross in a Time of COVID-19 and Trump” makes reference to Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’s On Death and Dying, which is a book that posits that people progress through stages of grief, namely: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and finally acceptance. He notes that both the citizens in The Plague and President Trump in his response to COVID-19 follow these stages. According to Schultz:

When the plague first breaks out in Camus’ novel, denial was the word of the day. So too was it with Donald Trump….

Plagues are not what happen to us, it happens to the other, the stranger. He is the one who brought it to us, be he the vagabond, the foreigner, the immigrant, or simply someone who is not us. For Trump, COVID-19 is the Chinese disease. Plagues are not homegrown directed at the righteous. Plagues from Biblical times have been brought as a revenge by God against a people who did something wrong, yet we are the innocent ones….

Denial takes many shapes. It is not simply denial that the plague exists, but that if it does, it will be short term. It will be not too bad as Trump said of COVID-19, or maybe a few cases will increase or go down, or whatever. It will be short-lived; we can reopen America and go back to work soon….

Maybe it will end soon as the president hopes. But as reporters questioned his responses, Trump lashed out, angered that anyone could question his administration or its competence….

If denial and anger do not work, bargaining might work. COVID-19 is a test of American character and resolve, proof of the superiority of our way of life. Pull together, like we did during WW II, and it will be the good plague, the one that transcends partisanship and brings us together in death and sacrifice. We can win this good fight, deluding ourselves into thinking that self-exile was a product of free will and not necessity. Bargaining is also the name of the game when it comes to states receiving needed supplies. Trump has demanded that governors be grateful in return for help….

[Finally, it must be realized] death is not a choice. As seen first in Italy and now in New York City, the solemnity of funerals turned into depression and acceptance. Depression and acceptance at the prospect that deaths would occur there, but nationwide too that 100,000 to 200,000 will die….

What we learn from reading The Stranger and The Plague is that there is a script to human nature. It is the script of Kübler-Ross that plays out with every tragedy. How we respond to events like COVID-19 is like living in the movie Groundhog Day, where we simply relive and reenact a series of scripted events that prove that Hegel was correct – the only thing we learn from history is that we don’t learn from history.

Dr. Mathew R. John writes in The Week of “takeaways” from The Plague that should make us smarter during the pandemic:

There have been many reviews suggesting that Camus alluded to the Nazi invasion of France as The Plague, while few others have commented that the use of the term is a metaphor for life itself. However, the description of the plague as a disease in itself is so comprehensive and convincing that one cannot resist reading the novel in its most direct way possible, that of the narrative of an epidemic.

To waste no more time on introductions, here are some of the key insights from the novel.

1. The larger historical landscape

Through the narrative of Dr. Rieux, Camus uses the initial chapters to position the current epidemic in Oran in a larger context by giving some details about previous plagues in history…. Also, in the final chapter, the author clearly mentions the possibility of recurrences of such plagues in the future. Thus Camus offers a model of understanding the catastrophe as an event in history rather than a singular challenge unmindful of time.

This is important because the current coronavirus pandemic appears as a pervasive and all-encompassing topic for all of us which seems to put every other event in the shadow. We are fully consumed by the thoughts of the pandemic while Camus suggests that need not be the case. Plagues are a part of human existence and disaster preparedness would be one of the best responses from our side.

2. An objective narrative

Many a time, in the book, the narrator seems to take extra effort to maintain the rigor of his narration, which reminds one of scientific pursuits….

Thus, Camus underlines the importance of objectivity and rigor while narrating a catastrophic event of great social impact.

3. The nature of calamities

A paragraph from one of the initial chapters reads thus – “A pestilence isn’t a thing made to man’s measure; therefore we tell ourselves that a pestilence is a mere bogey of the mind, a bad dream that will pass away. But it doesn’t always pass away and, from one bad dream to another, it is the men who pass away……”

And in the same page, “When a war breaks out, people say, ‘It’s too stupid; it can’t last long.’ But though a war may well be too stupid, that doesn’t prevent its lasting.”

Camus challenges our predisposition to attribute humanness to all events including calamities and to deny vehemently, the possibility of such events escalating into proportions fully beyond the scope of human imagination. In simple terms, he urges us to drop wishful thinking and self-denial of reality.

4. Optimal use of the resource of time

The author offers a defense against the repetitive unpredictable calamities which threaten our existence from time to time. That is a proper use of the available time at our disposal. To illustrate this point, he uses as examples Rieux’ silent and relatively unexpressed love towards his mother and his relationship with his friend who had died ‘without their friendship’s having had time to enter fully into the life of either’.

Camus suggests that an ever so valuable and fulfilling entity that one can sometimes attain, in an unpredictable world is human love. For people with greater and more abstract aspirations above the level of the human individual, time is a limiting factor. Our life is inherently unpredictable with the possibilities of recurring plagues and calamities and hence, finding time for love and happiness is crucial.

5. From heroism to decency

The narrative avoids repetitively the tendency to identify heroes in the town’s resistance against the plague. Rieux makes this clear when he says – “I feel more fellowship with the defeated than with saints. Heroism and sanctity don’t really appeal to me, I imagine. What interests me is – being a man.”

Also in Rieux’s conversation with his journalist friend, Rambert, “there is no question of heroism in all this. It is a matter of common decency……but the only means of fighting a plague is common decency.” Throughout the narrative, people are portrayed in a realistic manner without any sort of hero/villain divide and there are efforts to visualize the plague through the eyes of different characters, with their own different meanings. While downplaying the ‘hero’ concept, Camus characterizes the healers of the plague as people who, while unable to be saints, refuse to bow down to pestilences. By avoiding the propensity for idolatry, one is left with a much more realistic perspective on human responses in the wake of a disaster.

6. The significance of a chronicle

Many volunteers in the resistance against the Plague succumb to it including Jean Tarrou, Magistrate Othon and Father Paneloux. When the plague finally comes to an end, the dead are forgotten in the egoistic, but necessary celebrations of the living. Dr. Rieux decides to compile the chronicle amid the celebrations ‘to bear witness to those plague-stricken people, so that some memorial of the injustice and outrage done them might endure’. Also, he wants to state, ‘quite simply, what we learn in a time of pestilence’. The well-known medical information website, Medscape, has made an expanding list of all the frontline healthcare workers who succumbed to COVID-19. It is an effort to remember, and remember we must.

In closing, in memoriam for those whom Camus would have counted true heroes, here is the Medscape list of healthcare workers who succumbed to COVID-19.

QUOTATIONS FROM THE PLAGUE

(page numbers are from the 1972 Viking edition)

There have been as many plagues as wars; yet plagues and wars always take people by surprise.

When a war breaks out, people say: “It’s stupid; it can’t last long.” But though war may be “stupid,” that doesn’t prevent its lasting. Stupidity has a knack of getting its way; as we would recognize if we were not always so much wrapped up in ourselves….

A pestilence isn’t a thing made to man’s measure; therefore, we tend to tell ourselves that it is a mere bogey of the mind, a bad dream that will pass away. But it doesn’t pass away, but it is men that pass away…. Our town is not more to blame than any others. We just forgot to be modest, and we thought that everything still was possible for us; which presupposed that pestilences would not really take place, and so we went on doing business, arranged for journeys, and formed views. How should we have given a thought to anything like plague, which rules out any future, cancels journeys, silences the exchange of views. We fancied ourselves free, but no one will ever be free so long as there are pestilences that can take away life at a moment’s notice.

(The Plague, page 36).

From now on, it can be said that plague was the concern of all of us. Hitherto, surprised as a person may have been by the strange events, each individual had gone about his or her business as usual, so far as possible. But once the town gates were shut, everyone realized that all were, so to speak, in the same boat, and each would have to adapt to the new conditions of life. Thus, a feeling normally as individual as the ache of separation from a loved one became a feeling in which all shared and – together with fear – the greatest affliction of our period of exile.

One of the most meaningful consequences of quarantine was this sudden separation befalling people who were completely unprepared. Mothers and children, lovers, husbands and wives, who had a few days previously taken it for granted that their parting would be a short one, who had kissed one another good-by on the platform and exchanged a few trivial remarks, sure as they were of seeing one another again after a few days or, at most, a few weeks, duped by our blind human faith in the near future and little if at all diverted from their normal interests by this leave-taking – all these people found themselves, without the least warning, hopelessly cut off, prevented from seeing one another again….

(The Plague, pages 63-64).

For most people it was obvious that the separation must last until the end of the epidemic, and for every one of us the ruling emotion of life took on a new aspect. Husbands who had had complete faith in their wives found, to their surprise, that they were jealous; and lovers had the same experience. Men who had pictured themselves as Don Juans became models of fidelity. Sons who had lived beside their mothers hardly giving them a glance fell to picturing with poignant regret each wrinkle in the absent face that memory cast upon the screen. This drastic, clean-cut deprivation and our complete ignorance of what the future held in store had taken us unawares; we were unable to react against the mute appeal of presences, still so near and already so far, which haunted us daylong. In fact, our suffering was twofold; our own to start with, and then the imagined suffering of the absent one, son, mother, wife, or mistress.

Under other circumstances our townsfolk would probably have found an outlet in increased activity, a more sociable life. But the plague forced inactivity on them, limiting their movements to the same dull round inside the town, and throwing them, day after day, on the illusive solace of their memories….

Thus the first thing that the plague brought to our town was exile – a sensation of a void within that never left us, an irrational longing to hark back to the past or else to speed up the march of time, and keen shafts of memory that stung like fire…. [Sometimes we would try to imagine contact with our loved ones, and] then we realized with regret that the separation was destined to continue, and we had no choice but to come to terms with the days ahead. We returned to our prison-house, recognizing that we had nothing left us but the past….

(The Plague, pages 66-67).

Hostile to the past, impatient of the present, and cheated of the future, we were much like those forced to live behind prison bars.

(The Plague, page 69).

[T]his misfortune which had come from outside and befallen a whole town did more than inflict on us an unmerited distress with which we might well be indignant. It also incited us to create our own suffering and thus to accept frustration as a natural state. This was one of the tricks the pestilence had of diverting attention and confounding issues.

Thus each of us had to be content to live only for the day, alone under the vast indifference of the sky. This sense of being abandoned, which might in time have given characters a finer temper, began, however, by sapping them to the point of futility….

Moreover, in this extremity of solitude none could count on any help from his neighbor; each had to bear the load of his troubles alone.

(The Plague, pages 70-71).

At first the fact of being cut off from the outside world was accepted with a more or less good grace, much as people would have put up with any other temporary inconvenience that interfered with only a few of their habits. But, now they had abruptly become aware that they were undergoing a sort of incarceration under that blue dome of sky, already beginning to sizzle in the fires of summer, they had a vague sensation that their whole lives were threatened by the present turn of events, and in the evening, when the cooler air revived their energy, this feeling of being locked in like criminals prompted them sometimes to foolhardy acts.

(The Plague, page 95).

Plague kills all colors, vetoes all pleasures.

(The Plague, page 107).

In the early days, when the people thought this epidemic was much like others, religion held its ground. But once they realized their instant peril, they gave their thoughts to pleasure. And all the hideous fears that stamped their faces in the daytime are transformed in the fiery, dusty nightfall into a sort of hectic exaltation, and unkempt freedom that fevers their blood.

(The Plague, page 115).

The plague has its good side; it opens men’s eyes and forces them to take thought…. It helps men to rise above themselves.

(The Plague, page 119).

Week by week the prisoners put up what fight they could. Some even contrived to fancy they were still behaving as free people. But actually it would have been truer to say that by this time, the plague had swallowed up everything and everyone. No longer were there individual destinies; only a collective destiny, made up of plague and emotions shared by all. Strongest of these were exile and deprivation, with cross-currents of revolt and fear.

(The Plague, page 157).

Nothing is less sensational than pestilence, and by reason of its duration, it is monotonous. In the memories of those who lived through a time of pestilence, the grim days do not stand out like vivid flames, ravenous and inextinguishable, beaconing a troubled sky, but rather like the slow, deliberate progress of some monstrous thing crushing out all upon its path.

The plague is above all a shrewd, unflagging adversary; a skilled organizer, doing its work thoroughly and well.

(The Plague, page 169).

In times of plague, we waste away emotionally as well as physically. At the beginning we can vividly picture the absent ones. Although we can recall the faces, the smiles and voices, we had trouble in picturing what he or she might be doing at the moment. At these times, memory played its part, but imagination failed us. During the second phase, our memories failed us, as well.

Thus, while during the beginning we were apt to complain that only shadows remained, we now have come to learn that even shadows can waste away.

None of us are capable of an exalted emotion; all have trite, monotonous feelings.

The furious revolt against the frustrations of the quarantine have given place to a vast despondency, not to be taken for resignation, though it is none the less a sort of passive and provisional acquiescence.

Our fellow citizens have fallen in line, adapted themselves to the situation, because there is no way of doing otherwise. Naturally they retained the attitudes of sadness and suffering, but they had ceased to feel their sting. Indeed, to some, this was precisely the most disheartening thing: that the habit of despair is worse than despair itself.

(The Plague, pages 169-170).

You can see people standing around, listless, indifferent, and looking so bored that, because of them, the whole town seemed like a railway waiting-room.

Those who had jobs went about them at the exact tempo of the plague, with dreary perseverance.

Without memories, without hope, we lived for the moment only. The here and now had come to mean everything to us. For there is no denying that the plague had gradually killed off in all of us the faculty not of love only but even of friendship. Naturally enough, since love asks something of the future, and nothing was left us but a series of present moments.

(The Plague, page 171).

So completely were we dominated by the plague that sometimes the one thing we aspired to was the long sleep it would bring, and we caught ourselves thinking: “Might as well catch it and be done with it!” But really we were asleep already; this whole period was no more than a long night’s slumber. Our community was peopled with nothing but sleepwalkers.

(The Plague, page 172).

What impression did these exiles of the plague make on the observer? The answer is simple; they made none. Or, to put it differently, they looked like everybody else, nondescript. They shard in the torpor of the town and in its puerile agitations. They lost every trace of a critical spirit, while gaining an air of sang-froid…. They ceased to make any choices for themselves plague leveled out discrimination. This could be seen by the way nobody troubled about the quality of the clothes or food he bought. Everything was taken as it came.

(The Plague, page 173).

Tarrou took Rambert into a small room, all the wall space of which was occupied by cupboards. Opening one, he took from a sterilizer two masks of cotton-wool enclosed in muslim, handed one to Rambert, and told him to put it on. Rambert asked if it was really any use. Tarrou said no, but it inspired confidence in others.

(The Plague, page 192).

Whenever any of them spoke through the mask, the muslim bulged and grew moist over the lips. This gave a sort of unreality to the conversation; it was like a colloquy of statues.

(The Plague, page 193).

At about this time, one was struck by the number of glossy, rubberized rain jackets to be seen. The reason was that our newspapers had informed us that two hundred years previously, during the great pestilences of southern Europe, the doctors wore oiled clothing as a safeguard against infection. The shops had seized this opportunity of unloading their stock of out-of-fashion waterproofs, which their purchasers fondly hoped would guarantee immunity from germs.

With the coming of All Souls’ Day, the cemeteries were left unvisited. In previous years the rather sickly smell of chrysanthemums had filled the streetcars, while long lines of women could be seen making pilgrimages to the places where members of the family were buried, to lay flowers on the graves. This was the day when they made amends for the oblivion and dereliction in which their dead had slept for many a long month. But in the plague year people no longer wished to be reminded of their dead. Because, indeed, they were thinking all too much about them as it was. There was no more question of revisiting them with a shade of regret and much melancholy. They were no longer the forsaken to whom, one day a year, you came to justify yourself. They were intruders whom you would rather forget. This is why the Day of the Dead this year was tacitly but willfully ignored. Each day was for us a Day of the Dead.

(The Plague, page 218).

Meanwhile the authorities had another cause for anxiety in the difficulty of maintaining the food-supply. Profiteers were taking a hand and purveying at enormous prices essential foodstuffs not available in the shops. The result was that poor families were in great straights, while the rich went short of practically nothing. Thus, whereas plague by its impartial ministrations should have promoted equality among our townsfolk, it now had the opposite effect and, thanks to the habitual conflict of cupidities, exacerbated the sense of injustice rankling in men’s hearts. They were assured, of course, of the inerrable equality of death, but nobody wanted that kind of equality.

(The Plague, page 220).

One of the main characters, Jean Tarrou, identifies plague with social injustice of any kind, but primarily capital punishment and other forms of murder, and near the end of the book, gives a long explanation of his principles:

I came to realize that I had the plague through all those long years in which, paradoxically, I’d believed with all my soul that I was fighting it. I learned that I had had an indirect hand in the deaths of other people; that I’d brought about their deaths by approving acts and principles which could only end that way. When I spoke about these things with other people, they told me not to be so squeamish; I should remember what great issues were at stake. I replied that the most eminent of the plague-stricken also have excellent arguments to justify what they do, and once I admitted the arguments of necessity and force majeure put forward by the less eminent, I couldn’t reject those of the eminent.

I’ve been ashamed ever since; I’ve realized that we all have plague, and I have lost my peace. And today I am still trying to find it; still trying to understand all those others and not to be the mortal enemy of anyone. I only know that one must do what one can to cease being plague-stricken, and that’s the only way in which we can hope for some peace or, failing that, a decent death. This and only this can bring relief to men and, if not save them, at least do them the least harm possible and even, sometimes, a little good. So that is why I resolved to have no truck with anything that, directly or indirectly, for good reasons or for bad, brings death to anyone or justifies others’ putting him or her to death.

Each of us have the plague within ourselves — no one, no one on earth is free from it. And I know, too, that we must keep endless watch on ourselves lest in a careless moment we breathe in somebody’s face and fasten the infection on him or her. What’s natural is the microbe. All the rest – health, integrity, purity (if you like) – is a product of the human will, of a vigilance that must never falter. The good man, the man who infects hardly anyone, is the man who has the fewest lapses of attention. And it needs tremendous will power, a never ending tension of the mind, to avoid such lapses.

I know I have no place in the world of today; once I’d definitely refused to kill, I doomed myself to an exile that can never end. I leave it to others to make history. I know, too, that I’m not qualified to pass judgment on others. There’s something lacking in my mental make up, and its lack prevents me from being a rational murderer. So it’s a deficiency, not a superiority. But as things are, I’m willing to be as I am; I’ve learned modesty. All I maintain is that on this earth there are pestilences and there are victims, and it’s up to us, so far as possible , not to join forces with the pestilences.

I’ve come to realize that all of our troubles spring from our failure to use plain, clean-cut language. So I resolved always to speak – and to act – quite clearly. That’s why I say there are pestilences and there are victims; no more than that.

Because of this way of seeing things, I have decided to take, in every predicament, the victims’ side, so as to reduce the damage done by me in the world. Among the victims, I can at least try to discover some degree of peace.

(The Plague, pages 234-237).

A loveless world is a dead world, and always there comes an hour when one is weary of prisons, of one’s work, and of devotion to duty, and all one craves for is a loved face, the warmth and wonder of a loving heart.

(The Plague, page 243).

All agreed that the amenities of the past couldn’t be restored at once; destruction is an easier, speedier process than reconstruction.

(The Plague, page 249).

Generally speaking, the epidemic was in retreat all along the line; the official communiques, which had at first encouraged no more than shadowy, half-hearted hopes, now confirmed the popular belief that the victory was won and the enemy abandoning his positions. Really, however, it is doubtful if this could be called a victory. All that could be said was that the disease seemed to be leaving as unaccountably as it had come.

on a closer view, you might notice that people looked less strained, and they occasionally smiled.

(The Plague, page 251).

It could be said that once the faintest stirring of hope became possible, the dominion of the plague was ended.

(The Plague, page 252).

Naturally our fellow citizens’ strongest desire was, and would be, to behave as if nothing had changed and for that reason nothing would be changed, in a sense. But — to look at it from another angle — one can’t forget everything, however great one’s wish to do so; the plague was bound to leave traces, anyhow, in people’s hearts.

(The Plague, page 259).